Bahnbrechende Messung der Expansion des Universums verändert eine langjährige Debatte

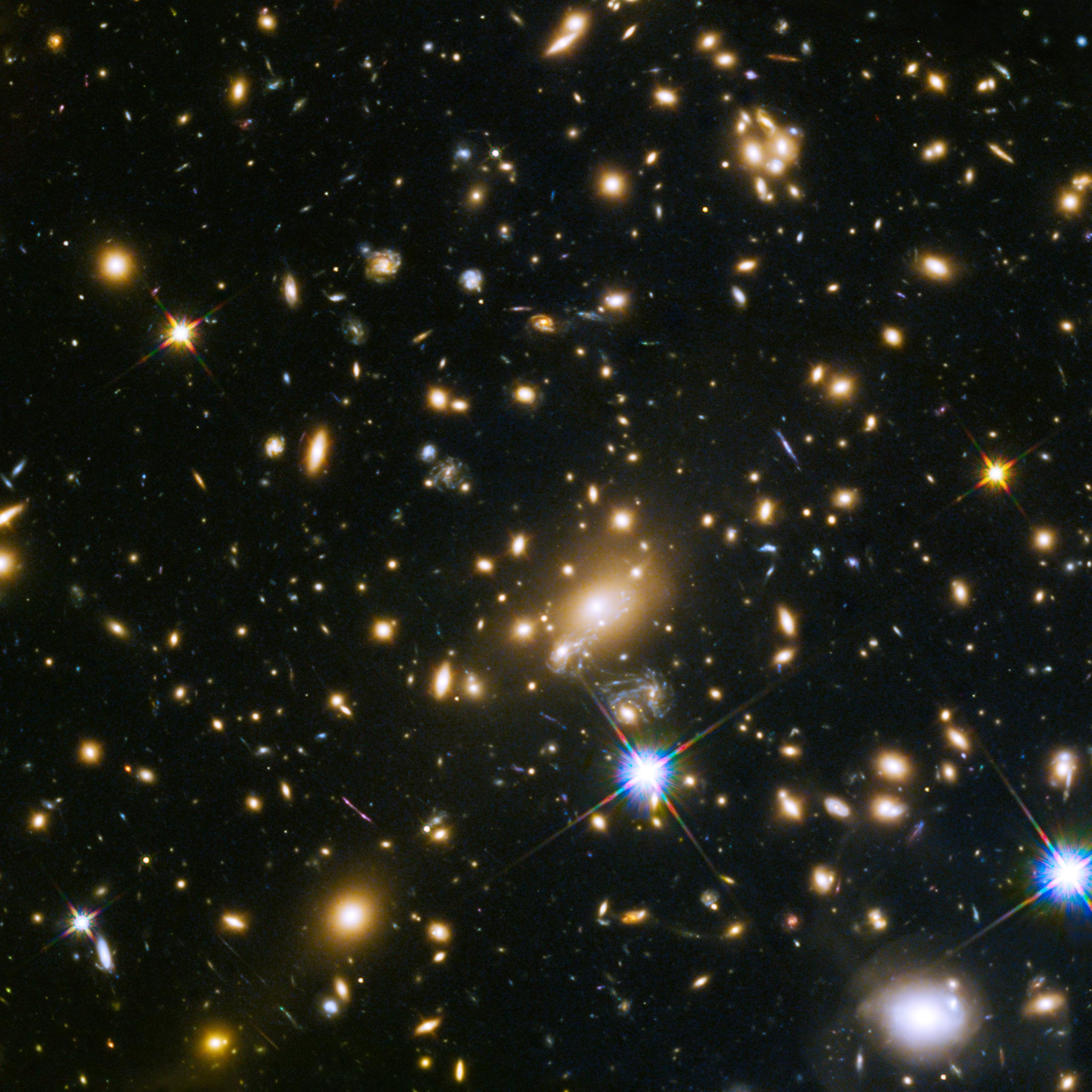

Dieses Bild zeigt den massereichen Galaxienhaufen MACS J1149.5+223, dessen Licht mehr als 5 Milliarden Jahre gebraucht hat, um uns zu erreichen. Die massive Masse des Clusters beugt das Licht entfernter Objekte. Das Licht dieser Objekte wurde durch Gravitationslinsen vergrößert und verzerrt. Der gleiche Effekt besteht darin, mehrere Bilder derselben entfernten Objekte zu erstellen. Bildnachweis: NASA, Europäische Weltraumorganisation, S.A.E. Rodney (John Hopkins University, USA) und Frontier SN Team; T. Treu (University of California, Los Angeles, USA), P. Kelly (UC Berkeley, USA) und das GLASS-Team; Lotus (STScI) und Frontierfields-Team; M. Postman (STScI) und das CLASH-Team; und Z. Levay (STScI)

Eine von der University of Minnesota geleitete Forschung könnte dabei helfen, das Alter des Universums genauer zu bestimmen.

Ein von der University of Minnesota Twin Cities geleitetes Team nutzte eine einzigartige Technik, um die Expansionsrate des Universums zu messen und lieferte Erkenntnisse, die dazu beitragen könnten, das Alter des Universums genauer zu bestimmen und Physikern und Astronomen dabei zu helfen, das Universum besser zu verstehen Kosmos.

Mithilfe von Daten einer vergrößerten Supernova mit mehreren Bildern ist es einem Team unter der Leitung von Forschern der University of Minnesota Twin Cities gelungen, mit einer einzigartigen Technik die Expansionsrate des Universums zu messen. Ihre Daten geben Einblick in eine langjährige Debatte auf diesem Gebiet und könnten Wissenschaftlern dabei helfen, das Alter des Universums genauer zu bestimmen und das Universum besser zu verstehen.

Die Arbeit ist in zwei Artikel unterteilt, die jeweils in veröffentlicht wurden WissenschaftenEs handelt sich um eine der besten peer-reviewten Fachzeitschriften der Welt Die Big Bang.

However, these two measurements differ by about 10 percent, which has caused widespread debate among physicists and astronomers. If both measurements are accurate, that means scientists’ current theory about the makeup of the universe is incomplete.

“If new, independent measurements confirm this disagreement between the two measurements of the Hubble constant, it would become a chink in the armor of our understanding of the cosmos,” said Patrick Kelly, lead author of both papers and an assistant professor in the University of Minnesota School of Physics and Astronomy. “The big question is if there is a possible issue with one or both of the measurements. Our research addresses that by using an independent, completely different way to measure the expansion rate of the Universe.”

The University of Minnesota-led team was able to calculate this value using data from a supernova discovered by Kelly in 2014—the first-ever example of a multiply-imaged supernova, meaning that the telescope captured four different images of the same cosmic event. After the discovery, teams around the world predicted that the supernova would reappear at a new position in 2015, and the University of Minnesota team detected this additional image.

These multiple images appeared because the supernova was gravitationally lensed by a galaxy cluster, a phenomenon in which mass from the cluster bends and magnifies light. By using the time delays between the appearances of the 2014 and 2015 images, the researchers were able to measure the Hubble Constant using a theory developed in 1964 by Norwegian astronomer Sjur Refsdal that had previously been impossible to put into practice.

The researchers’ findings don’t absolutely settle the debate, Kelly said, but they do provide more insight into the problem and bring physicists closer to obtaining the most accurate measurement of the Universe’s age.

“Our measurement is in better agreement with the value from the cosmic microwave background, although—given the uncertainties—it does not rule out the measurement from the local distance ladder,” Kelly said. “If observations of future supernovae that are also gravitationally lensed by clusters yield a similar result, then it would identify an issue with the current supernova value, or our understanding of galaxy-cluster dark matter.”

Using the same data, the researchers found that some current models of galaxy-cluster dark matter were able to explain their observations of the supernovae. This allowed them to determine the most accurate models for the locations of dark matter in the galaxy cluster, a question that has long plagued astronomers.

References:

“Constraints on the Hubble constant from Supernova Refsdal’s reappearance” by Patrick L. Kelly, Steven Rodney, Tommaso Treu, Masamune Oguri, Wenlei Chen, Adi Zitrin, Simon Birrer, Vivien Bonvin, Luc Dessart, Jose M. Diego, Alexei V. Filippenko, Ryan J. Foley, Daniel Gilman, Jens Hjorth, Mathilde Jauzac, Kaisey Mandel, Martin Millon, Justin Pierel, Keren Sharon, Stephen Thorp, Liliya Williams, Tom Broadhurst, Alan Dressler, Or Graur, Saurabh Jha, Curtis McCully, Marc Postman, Kasper Borello Schmidt, Brad E. Tucker and Anja von der Linden, 11 May 2023, Science.

DOI: 10.1126/science.abh1322

“The Magnificent Five Images of Supernova Refsdal: Time Delay and Magnification Measurements” by Patrick L. Kelly, Steven Rodney, Tommaso Treu, Simon Birrer, Vivien Bonvin, Luc Dessart, Ryan J. Foley, Alexei V. Filippenko, Daniel Gilman, Saurabh Jha, Jens Hjorth, Kaisey Mandel, Martin Millon, Justin Pierel, Stephen Thorp, Adi Zitrin, Tom Broadhurst, Wenlei Chen, Jose M. Diego, Alan Dressler, Or Graur, Mathilde Jauzac, Matthew A. Malkan, Curtis McCully, Masamune Oguri, Marc Postman, Kasper Borello Schmidt, Keren Sharon, Brad E. Tucker, Anja von der Linden and Joachim Wambsganss, 11 May 2023, The Astrophysical Journal.

DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ac4ccb

This research was funded primarily by NASA through the Space Telescope Science Institute and the National Science Foundation.

In addition to Kelly, the team included researchers from the University of Minnesota’s Minnesota Institute for Astrophysics; the University of South Carolina; the University of California, Los Angeles; Stanford University; the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne; Sorbonne University; the University of California, Berkeley; the University of Toronto; Rutgers University; the University of Copenhagen; the University of Cambridge; the Kavli Institute for Cosmology; Ben-Gurion University of the Negev; University of the Basque Country; the University of Cantabria; Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas (the Spanish National Research Council); the Observatories of the Carnegie Institution for Science; the University of Portsmouth; Durham University; the University of California, Santa Barbara; the University of Tokyo; the Space Telescope Science Institute; the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam; the University of Michigan; Australian National University; Stony Brook University; Heidelberg University; and Chiba University.

„Musikfan. Sehr bescheidener Entdecker. Analytiker. Reisefreak. Extremer Fernsehlehrer. Gamer.“